Heeramandi lives on lavish otherworldliness from start to finish. Sanjay Leela Bhansali, who is directing his first streaming series, seems to be insisting that we miss the big screen even more. Mallikajaan, a prostitute in Lahore, weeps in front of a fireplace while flinging pieces of costly jewelry into the sickly flames. The entire mansion is shrouded in unearthly shadows. When a voice shouts out and a curtain opens, we see the haveli across, its inside ablaze with festivity and laughing. It is a spellbinding moment in the series, expressing more by the interplay of light and darkness than any narrative twist or lyrical word.

Heermandi contains a significant amount of poetry. As usual — and perhaps inspired by the place and the period, pre-Independence India — Bhansali expresses his admiration for the Sufi and Urdu greats. The song ‘Sakal Ban,’ which announces the approach of spring, is based on an Amir Khusrow poem and includes references to Ghalib, Mir, Zafar, and Niyazi. Alamzeb (Sharmin Sehgal), one of the main protagonists, is an aspiring poetess, similar to Rekha in Umrao Jaan (1981). There are conversational clusters that are nearly identical to verse. “I will serve you couplets for breakfast and poems for lunch,” Alamzeb tells her fiancée. She may just as well be addressing the spectator.

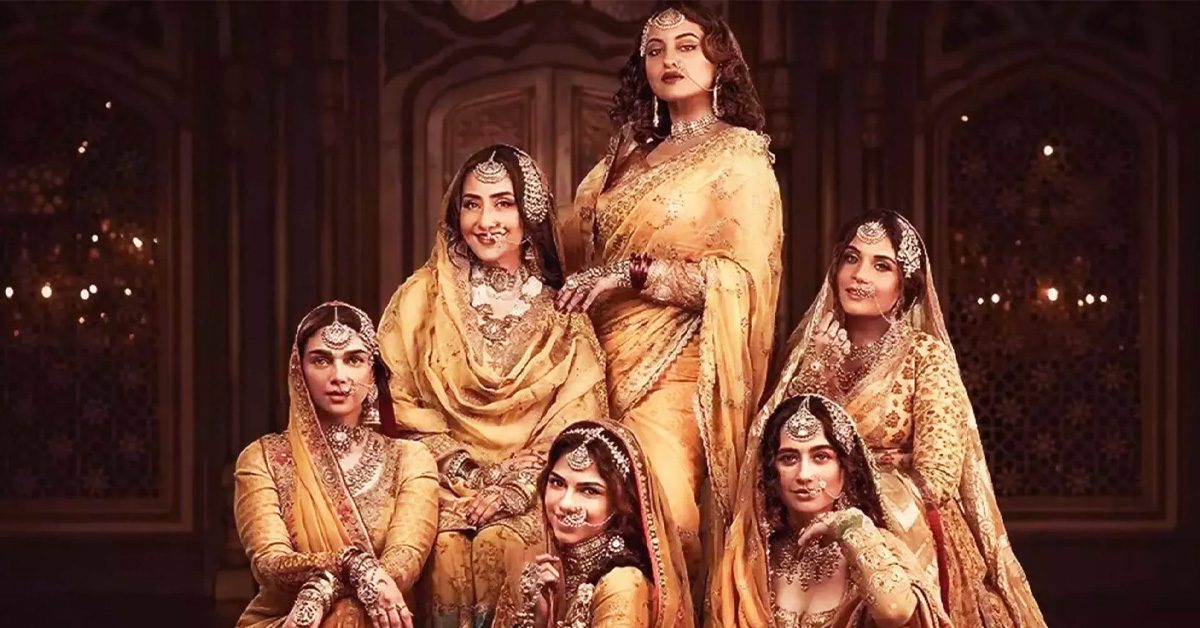

Alamzeb is the daughter of Mallikajaan (Manisha Koirala), the owner of Shahi Mahal, an upscale brothel in Lahore’s pleasure area, Heera Mandi.

Mallikajaan has another daughter, Bibbo (Aditi Rao Hydari), who is a renowned singer and revolutionary spy. It’s the 1940s, and rebellion against the Raj is gaining momentum. The uncouth nawabs serve their foreign masters for titles and security. However, it is the courtesans who truly call the tunes, protecting their patrons’ secrets and, on occasion, leading them to destruction.

A succession of dramatic flashbacks puts the story in action. Mallikajaan, it turns out, has her own secrets, including a heinous act from her past that has been hidden and hushed with the help of the debauched nawab Zulfikar (Shekhar Suman). Once discovered, it sparks a power struggle between her and Fareedan (Sonakshi Sinha), a rival courtesan who settles up at Heera Mandi and begins ruffling old and new feathers.

Heeramandi – The narrative revolves around Fareedan’s intricate vengeance plots, an uncomfortably developing romance between Alamzeb and a rebellious young nawab, Tajdar (Taaha Shah), and the revolutionaries’ agitation. Cartwright (Jason Shah), the wicked police superintendent, keeps an eye out for bones.

Bhansali and his writers take their time bringing the many strands together. Despite the stunning sights and sounds on display, the wait grows lengthy. It doesn’t help that the exciting political backdrop of the time is drawn in broad strokes (no mention of the Muslim League or the quest for an independent Pakistan state).

Heera Mandi, a genuine area in Lahore, was founded in Mughal times, and its courtesans have amassed significant money and power over the years.

There is an interesting history of tawaifs helping to the liberation movement (Bibbo’s role, for example, appears to be based on Azizun Bai, a Kanpur prostitute who battled the British during the 1857 insurrection). However, in directing our attention to these unsung heroes, Bhansali and his writers tend to go emotionally overboard, creating well-meaning but problematic comparisons between the characters and India during British rule. Zulfikar mocks Mallikajaan for his ‘divide and rule’ strategy. Bibbo compares us to birds in a gilded cage, which is similar to India: a golden bird in an imperial cage. In a strange scene, a funeral gathering evolves into an impromptu independence song, with atawaif’s emancipation via death compared to a nation attaining ‘azaadi’.

In Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), Alia Bhatt’s eponymous heroine fought for the rights of sex workers in 1960s Mumbai. The dancers and singers of Heeramandi are commonly accused of sex work, and the play delicately addresses this element of courtesan life. Mallikajaan runs a tight ship yet speaks up for herself in public. In court, she defends the kothas’ elevated social standing as centers of refinement and culture. Even Fareedan, in the height of her villainy, expresses unity and care for her peers.

Heeramandi, which was shot on a large budget, is just magnificent. Sudeep Chatterjee, Mahesh Limaye, Huenstang Mohapatra, and Ragul Dharuman are the four cinematographers behind the series.

Bhansali also pays heartfelt tributes to classics like Mughal-E-Azam and Pakeezah — the pirouetting dancers on rooftops could belong in Kamal Amrohi’s film — and there is a passing nod to KL Saigal, who played the first Hindi Devdas onscreen, a legacy continued by Dilip Kumar and later Shah Rukh Khan in Bhansali’s own 2002 film.

Fardeen Khan radiates kohl-eyed menace as the nawab Wali Mohammed, while Koirala surrenders body and soul to Mallikajaan, ekeing out morsels of compassion from an inflated part. Nivedita Bhargava and Jayati Bhatia are lovely as the gabby servants Satto and Phatto. Richa Chadha’s performance, with her loud and boisterous laughing, is too short-lived. The series might have remained with seasoned actors like Chadha and Sanjeeda Sheikh; instead, the key lovers, portrayed blankly by Segal and Shah, take up the majority of the duration. For its last episodes, Heermandi delves into the world of gothic abstraction that is Bhansali’s trademark.